Plant microbiomes

Photo by Adrian Lange on Unsplash

Photo by Adrian Lange on UnsplashPlant-associated microbial communities tightly interact with their host, and play a fundamental role in the regulation of important biological processes such as plant growth and development, response to pests and pathogens, stress tolerance, nutrient acquisition, and response to adverse environmental conditions. The consequences of plant-microbiome interactions extend beyond the host plant itself, influencing the functional traits of both plants and the ecological community with important effects on the ecosystem. This strong bound between the plant and its microbiome places the term “plant health” into a new perspective, where the relationship between plants and their enemies has to be expanded to consider the complex array of interaction with the inhabitants of the plant microbiome. Thus, microbiome science is not only transforming the way we understand plants, but also the way we approach plant protection and biological control.

Our lab focuses on understanding the mechanisms that regulate the interactions between plants and their microbiome, and the consequences of these interactions on ecological communities. In particular, we focus on three major topics.

Abiotic and biotic stresses. Plants are constantly exposed to stressors, and so do their microbiomes. When plants experience drought, herbivory, or the attack from a pathogen they are able to recruit microorganisms from the environment via exudates and VOCs. Our lab is contributing to understanding the consequences of plant stresses on the plant microbiomes, and the mechanisms that plants and their associated microbes exploit to help counteracting different stressors.

Genome-microbiome interactions. Our results are clear: plant genotype plays a major role in assembling plant microbiomes. These results are supported by the extensive research in this field. However, we still know a little about the mechanisms behind this genotype-driven effect on the assembly of plant microbiomes. Our lab is working on dissecting the genetic architecture that plants use to recruit their own microbiome.

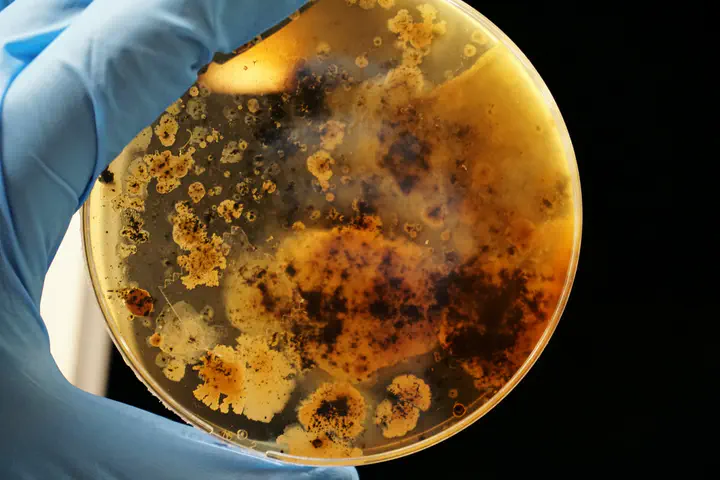

Dysbiosis. Sometimes, plant health status is difficult to be explained simply by the presence/absence of a plant pathogen. These multifactorial diseases are the result of the occurrence of several factors. Our case study, the Kiwifruit Vine Decline Syndrome, is a prime example of a disease with a very complex aetiology. One of the hypotheses we are exploring is that these multifactorial diseases might be the result of an unbalance in the plant-associated microbial communities, which can lead to a cascade of events resulting in plant diseases. Our lab is using KVDS and other plant diseases as models to understand origin and mechanisms behind the alteration of plant microbiomes that generate a disease.